A fragment of bird song turns George Meredith's head and he watches a skylark ascend, singing. He turns what he beholds or imagines into verse. Years later, Ralph Vaughan Williams reads the poem and is compelled to compose a piece of music for violin, the lark, and piano. Marie Hall helps Vaughan Williams illustrate the flight and song of the lark through the medium of her instrument. Later, the composer orchestrates the piece and that is mostly how we know The Lark Ascending today. "The silver chain of sound" reverberates from bird song to idea to poem to duet to orchestral piece to all of the recorded and unrecorded interpretations and inspirations since.

In 1982, while living on 5th Street in Santa Monica, I watched Sam Waterston play J. Robert Oppenheimer on the BBC Series, and thought, "I must write a song about Oppenheimer". The process of writing the song commenced.

The only book I could find about the Manhattan Project was Robert Jungk's personal account, Brighter Thank A Thousand Suns. I checked that book out of the library with a copy of John Donne's Holy Sonnets. The Holy Sonnets, especially XIV, gave me the idea for the framework and form of the lyrics and musical parts along with a literal quotation. The rest of the song worked its own way out.

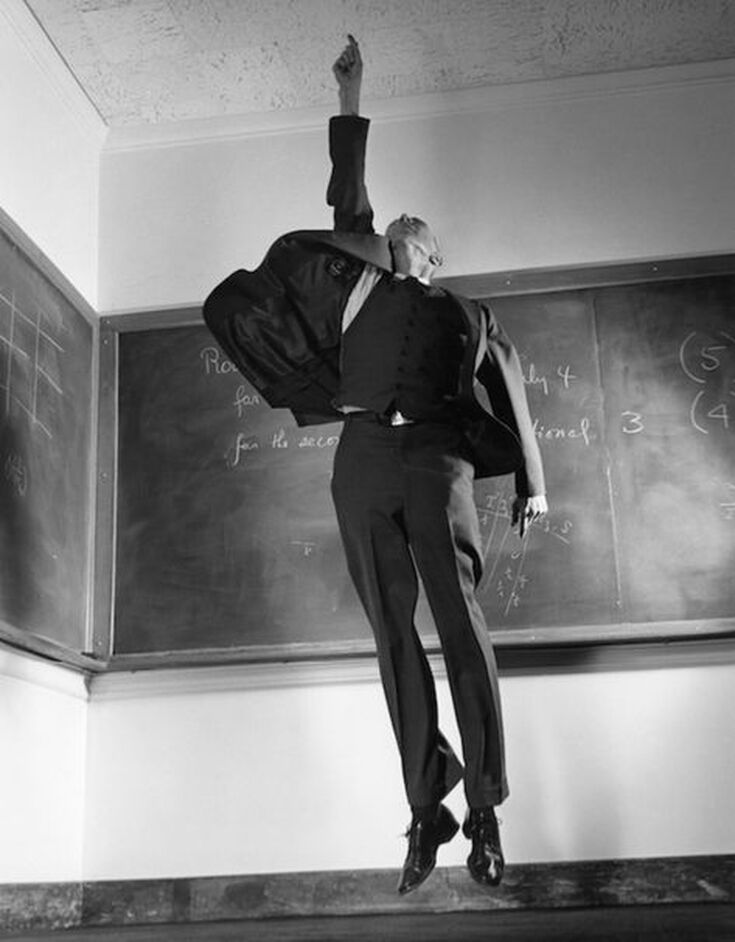

I had no inkling at first thought that I would build the song around the concept of Trinity, that I would regularly perform the song at anti-nuclear rallies over the next couple of years, or that a decade later I'd become friends with two physicists who'd worked on the Manhattan Project and knew Oppenheimer. One of those men was Francis Low (who accompanied me on piano in empty classrooms as I was reviving my vocal chops) and he worked at Oak Ridge in Tennessee. The other was Tony French who I was shocked to learn (when I finally asked him exactly what it was he did at Los Alamos) that he was Edward Teller's assistant. I've since wished that I'd asked him more but at that moment, I checked my curiosity.

I also never could have guessed that someone I gave a copy of my brand spanking new Souvenir CD (for which I finally recorded the Oppenheimer song) would take my conceptual framework and, without acknowledgement, turn it into a libretto for an acclaimed opera.

But that's another story. But not unrelated to the question of where ideas come from, the creative process, and working through that process. And it is work. A lot of work. But not the kind of work that you can always point to or assess by how many hours are spent on sets of tasks laid out on a particular schedule. Working through the creative process is a matter of opening up to chance, following your nose, picking up books at random, turning left instead of right down an unfamiliar street, and browsing, lots of browsing through printed words, pictures, videos, recordings, and whatnot, and paying attention to something that leaps out and says, I am your next step. Pay attention to me.

That's one part of the work. Grazing for clues but not too intently.

I often graze on rather than read books and I am not a fast reader, unless I’ve found a page turner. I read contemplatively by which I mean that I'll read a little and then reflect on it. Inevitably, I'll go down rabbit holes, looking up words I don't know, chasing down references. One distraction after another. I don't mind so much because I enjoy grazing books and am easily distracted.

Every once in a while, I’ll re-read Ray Bradbury. I love his poetic fiction but his introductions are worth the price of each entire book and are directed squarely at writers, or really anyone involved in the creative process.

His introduction to Dandelion Wine opens as follows:

“This book, like most of my books and stories, was a surprise. I began to learn the nature of such surprises, thank God, when I was fairly young as a writer. Before that, like every beginner, I thought you could beat, pummel, and thrash an idea into existence. Under such treatment, of course, any decent idea folds up its paws, turns on its back, fixes its eyes on eternity, and dies.”

A couple of pages later, he continues:

“Thus I fell into surprise. No one told me to surprise myself, I might add. I came on the old and best ways of writing through ignorance and experiment and was startled when truths leaped out of bushes like quail before gunshot. I blundered into creativity as blindly as any child learning to walk and see. I learned to let my senses and my Past tell me all that was somehow true.”

I firmly believe that creativity demands hours of practice and the discipline to settle down and do the actual work of designing, building and polishing any creative form. But when it comes to conjuring ideas, I surrender to magic, instinct and discovery.

Worth listening to:

The Rest Is History Podcast— Oppenheimer: The Father of the Atom Bomb and The Witch Hunt.

the BBC Series

RSS Feed

RSS Feed